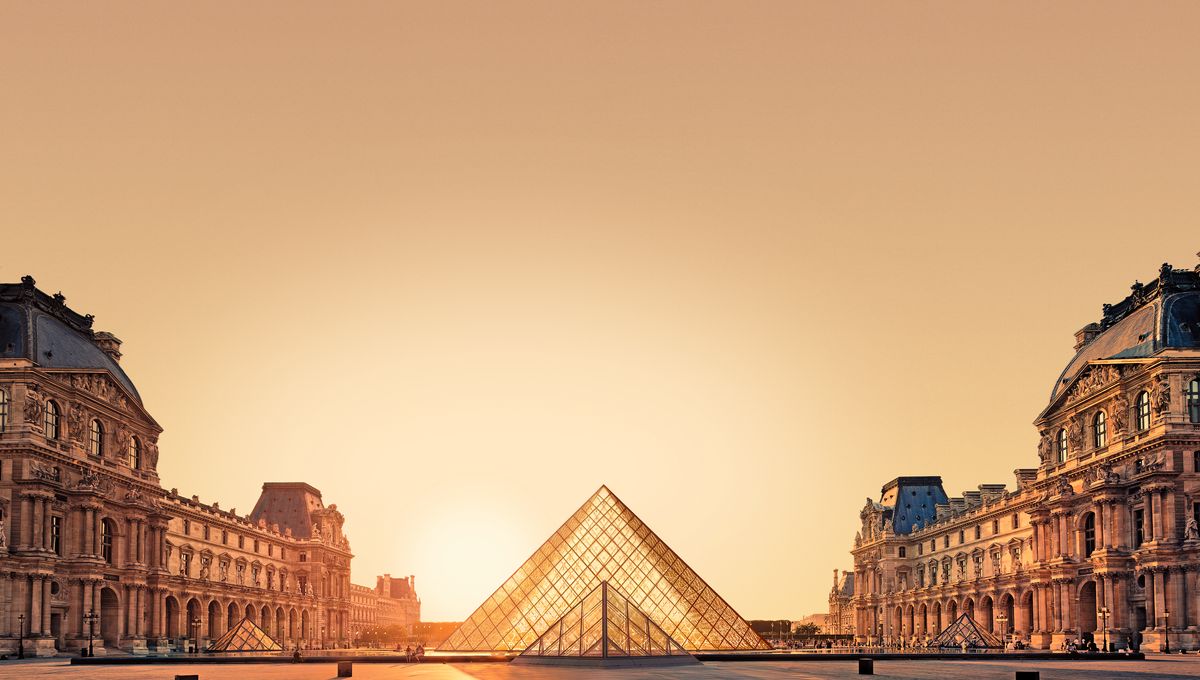

A pyramid for a symbolCour Napoléon & Pyramid

In the centre of the Cour Napoléon stands the most visible product of the vast ‘Grand Louvre’ project that modernised the museum in the 1980s: the Louvre's Pyramid, an architectural feat that has come to symbolise the museum itself.

A monumental entrance in the shape of a pyramid! What a bold undertaking indeed on the part of the Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei, to transform the very heart of the palace. His spectacular creation made the Louvre one of the rare museums to boast a work of art for an entrance hall. Here, we look back on this incredible metamorphosis that took place in the 1980s.

The Grand Louvre

Imagine the Louvre without its Pyramid, without its underground shopping centre, without its Richelieu wing (occupied at the time by the Ministry of Finance). In the Cour Napoléon, where the Pyramid now stands, were two small parks designed in the 19th century by Hector Lefuel, architect to Napoleon III, and a car park.

The Louvre of the 1980s was very different to today’s museum. With the number of visitors growing and the museum increasingly ill adapted to accommodating them, the Grand Louvre project aimed to both modernise and expand the premises.

In July 1983, I.M. Pei, who had already designed extensions for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, was appointed architect for the Grand Louvre project, which had been commissioned by French President François Mitterrand in 1981. Pei came up with the idea of a central underground lobby affording direct access to the museum’s three wings, which would transform visitor circulation inside the Louvre.

Its monumental entrance was to take an unusual form: a pyramid. What’s more, Pei also designed the new exhibition spaces in the Richelieu wing, the underground collection storerooms, and everything needed to welcome visitors in the belowground spaces: the ticket office, auditorium, cafés, bookshops – even a shopping centre providing an underground connection with the nearest metro station.

The pyramid polemic

This enormous construction project caused much debate and controversy. The Pyramid came in for a great deal of criticism, with its opponents denouncing its quite literally monumental proportions. Yet I.M. Pei’s work followed on from the Louvre’s long history of transformations. In his design, he respected the main lines and perspectives of the palace and its layout as a whole, whilst creating the most transparent, light and luminous structure possible. It was a technical feat – one that was carried off brilliantly. As Pei himself said: ‘My approach was that of a landscape designer rather than an architect. Le Nôtre was my main source of inspiration. The very design of the modules making up the Pyramid is French.’ It is based on simple shapes: the square and the triangle, which are repeated throughout the courtyard. They are echoed, too, in the shape of the pools surrounding the Pyramid, and even in the courtyard’s paving.

After four years’ work, with the participation of companies specialised in ships’ rigging to construct the metal frame, the Pyramid was inaugurated on 29 March 1989. It has since become the very symbol of the Louvre.

Related videos (in French)

'La Pyramide, le grand feuilleton du Louvre'

Did you know?

Truly transparent glass

I.M. Pei wanted the Pyramid’s glass sides to be absolutely transparent, so that the Louvre Palace’s historical facades could be admired from both inside and outside the Pyramid, in the Cour Napoléon. No fewer than two years of research were required to develop an extra-clear glass. The 2,000 m2 of 21-mm-thick glazing of exceptional quality were manufactured by the historic Saint-Gobain glass factory.

The Pyramid: key figures

Height: 21 m Base width: 35 m Base area: 1,000 m2 675 diamond-shaped glass panes and 118 triangular glass panes 6,000 bars and girders and 2,150 nodes forming the metal structure Weight of the steel structure: 95 tonnes Weight of the glazed aluminium frame: 105 tonnes

One good pyramid deserves another

The big Pyramid is not the only pyramid at the Louvre. There are two smaller ones in the Cour Napoléon, which bring light into the entrances of the museum’s three wings, as well as an inverted pyramid – another technical feat – at the museum’s entrance inside the underground Carrousel shopping centre. The latter’s glass surface is hidden among the greenery at the centre of the roundabout between the Cour Napoléon and the Carrousel Garden. Smaller than the large Pyramid but equally fascinating, the inverted pyramid is made up of 84 diamond-shaped panes of glass and 28 triangular panes. In total, then, the Louvre is home to no fewer than five pyramids!

A royal perspective

It has always been a challenge for landscape architects that, because of the bend in the Seine, the Louvre and the Tuileries Garden are not quite aligned, despite all the architectural solutions developed through the centuries. This can be observed from the Cour Napoléon: the Arc du Carrousel and the Pyramid do not line up. I.M. Pei came up with the solution of placing the statue of Louis XIV within this alignment, in front of the Pyramid, as the point of departure for a view that extends through the Tuileries Garden, across the Place de la Concorde, up the Champs-Elysées and all the way to the Grande Arche de la Défense.

More to explore

An Introduction to Islamic Art

The Cour Visconti - level -2 closed

From Royal Garden to Public Park

The Tuileries Garden