A Royal Setting for Egyptian AntiquitiesThe Musée Charles X

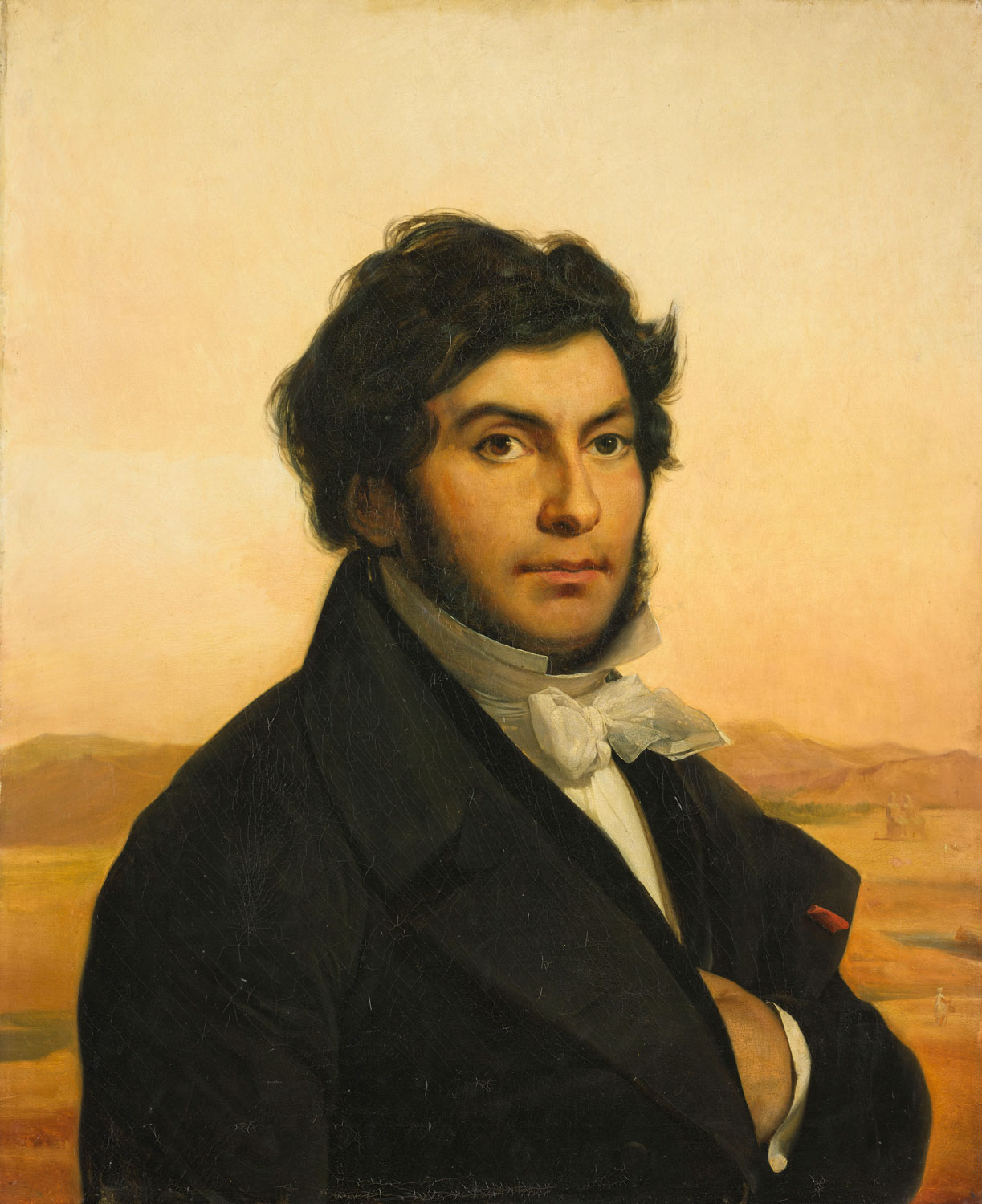

On 15 December 1827, a new museum was inaugurated in the Louvre palace. King Charles X was present for the occasion – unsurprisingly, as the new museum bore his name! He appointed a young scholar as its director: Jean-François Champollion, who had recently made a name for himself by deciphering the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and was now entrusted with the creation of the Louvre’s very first ‘Egyptian museum’.

The rediscovery of ancient Egypt

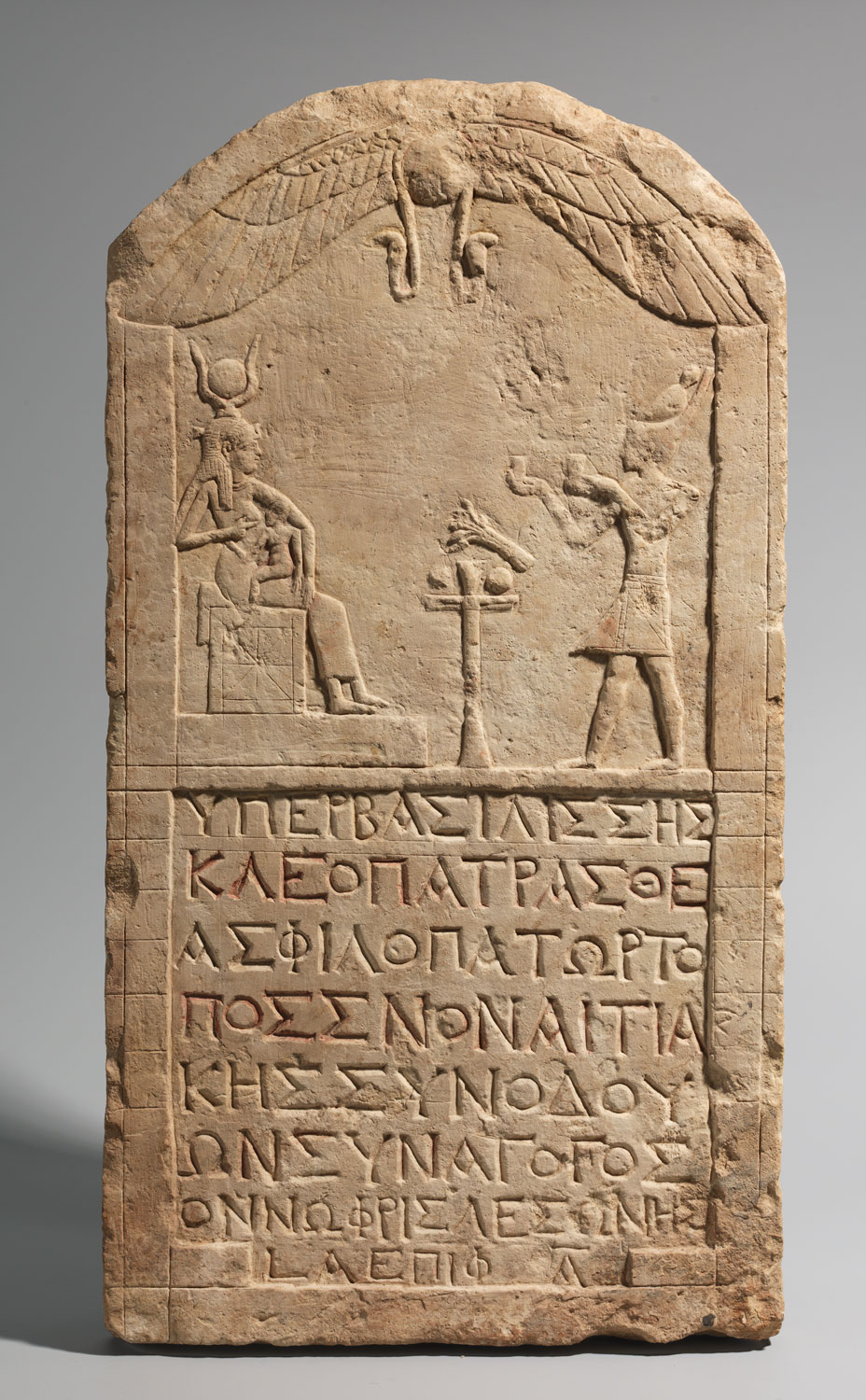

Western Europeans had long been fascinated by ancient Egypt, and this fascination continued to grow with Champollion’s discoveries. The Napoleonic military campaign in Egypt in the late 18th century had been accompanied by a scientific expedition involving the best researchers of the day; the resulting publications had advanced scientific knowledge of Egypt past and present but, despite a better understanding of the ancient artefacts, their true significance remained a mystery.

Champollion at the Louvre

This was the context in which Jean-François Champollion grew up. When he succeeded in deciphering the hieroglyphs in 1822, he was 32 years old. His discovery of the key to a forgotten language opened a new chapter in research with the emergence of the science of ‘Egyptology’. Hieroglyphic scripts were a precious source of first-hand accounts to be translated, analysed and understood! In his eagerness to spread knowledge of this ancient civilisation among his contemporaries, Champollion helped create the Egyptian museum in Turin, then convinced Charles X to purchase an Egyptian collection for the Louvre. The king appointed him curator of the new Egyptian museum; the only question was where it should be located.

A palatial home for the museum

The first quarter of the 19th century, when Egyptology was born, was a period of great change at the Louvre. As political regimes came and went, its status had fluctuated between royal (or imperial) residence and museum; as of the1820s, the museum began to dominate. Its expanding collections required the opening of new departments, which were like independent museums contained within the same huge building. They included the Galerie d’Angoulême displaying Renaissance and Modern sculptures, the Musée de la Marine, the Musée Assyrien and the Musée Charles X.

It was decided that the new department would be housed in a series of nine first-floor rooms on the Seine side of the palace, in what is now the Sully wing. These rooms were originally the queen’s apartments before becoming home to the Académie Royale d’Architecture and, finally, to the collections of Egyptian Antiquities.

A new setting for a new museum

The architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine had already been making changes to the Louvre for over 20 years when they were commissioned to create the Musée Charles X; the ensemble they designed still exists today. They linked the nine rooms together harmoniously with high openings suggesting triumphal arches, stucco imitating pink and white marble, and gilding to highlight the architectural details. The original display cases are still in place today.

The ceiling decorations were done by the greatest painters of the period, such as Antoine-Jean Gros, Horace Vernet and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The overall theme was antiquity, but the individual scenes ranged in inspiration from Egypt, Greece and Rome to medieval and Renaissance artefacts. The artists created allegorical depictions of pharaonic Egypt, deriving their ideas from Greco-Roman antiquity and biblical texts – paintings such as Study and Genuis Unveiling Ancient Egypt to Greece and Egypt Saved by Joseph.

And now?

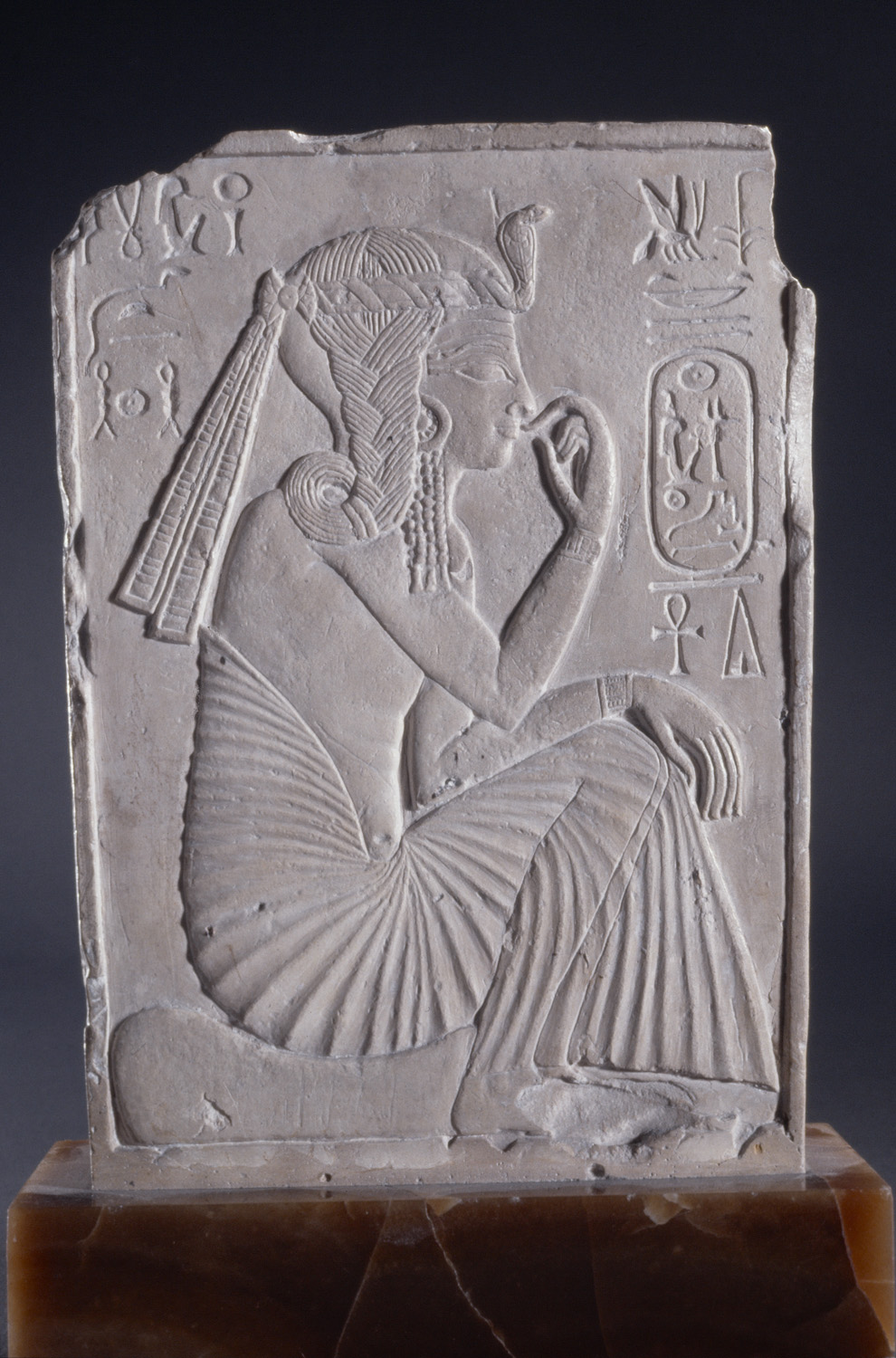

Our knowledge of ancient Egypt has changed beyond recognition since Champollion’s day and the Egyptian collection has expanded to cover two floors of the museum. The display includes several objects that were key to our understanding of the ancient Egyptian civilisation; those acquired by Champollion himself include the colossal statues of Ramesses II, the Bowl of General Djehuty and the relief carving from the tomb of Sethos I.

The rooms that once made up the Musée Charles X are now divided between the final section of the Egyptian display and the collections of Greek antiquities.

Masterpieces

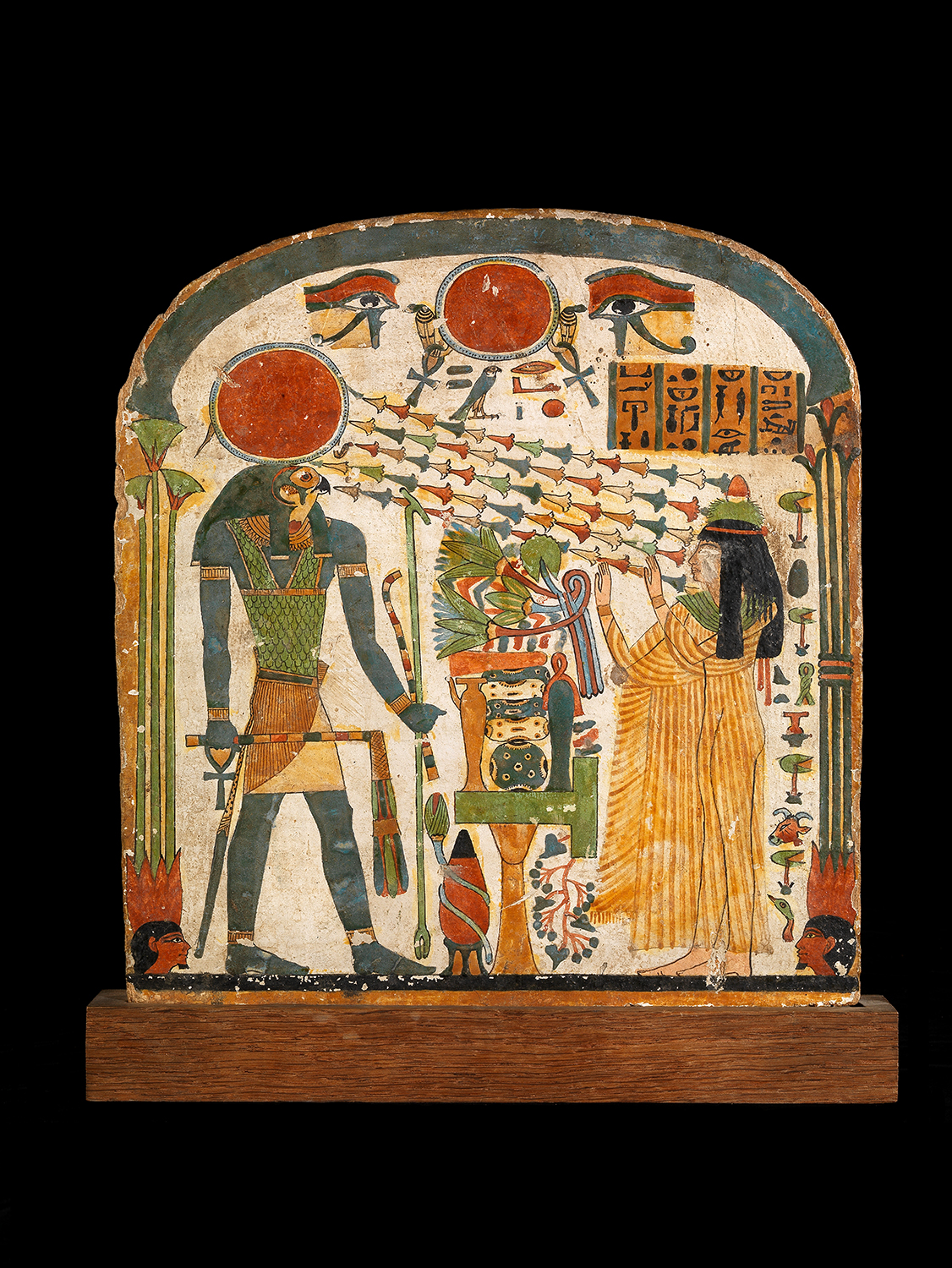

The rooms that once formed the Musée Charles X are now used to display a chronological presentation of the Ancient Egypt, covering the New Empire, the Third Intermediate Period, the Late Period and the Ptolemaic Period.

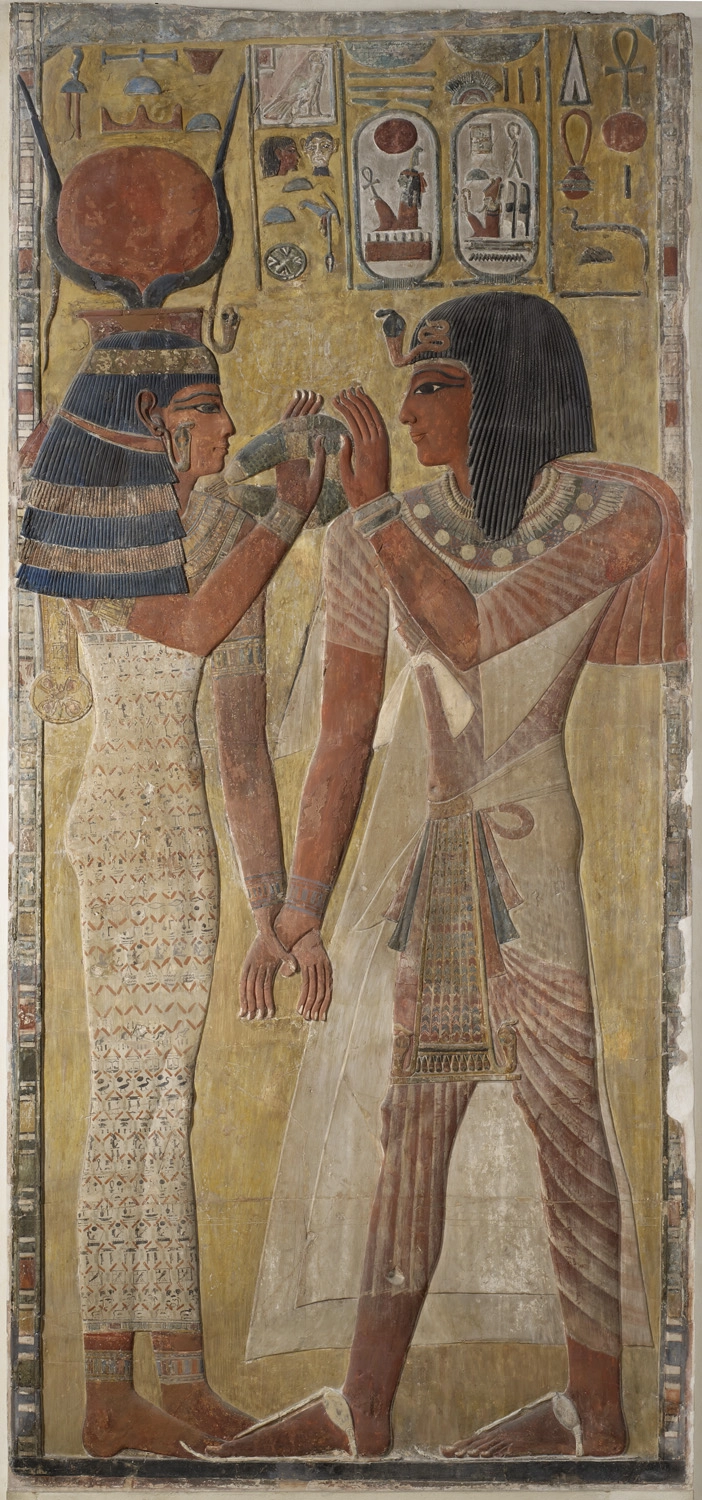

The goddess Hathor welcomes Seti I

1 sur 11

Did you know?

Brought down from above

The Apotheosis of Homer, by the great artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, originally graced a ceiling in the Musée Charles X. At the museum’s inauguration, Charles X reportedly forgot to look up at it! The painting was later taken down and replaced on the ceiling by a copy. The original work is now among the large 19th-century French paintings on display in the red rooms.

A divine pendant

This heavy pendant, a masterpiece of Egyptian goldwork, shows the three gods in one of the main triads of Egyptian mythology: the god Osiris, crouching on the central pillar, with his wife Isis and son Horus on either side. The three figures represent a founding myth of Egyptian religion: Osiris, killed by his brother Seth, was revived by his wife Isis who gave birth to their son Horus, the falcon god. The latter, who avenged his father and succeeded to the throne, symbolised victory over evil forces and the enduring power of the pharaohs.

More to explore

The Guardian of Egyptian Art

The Crypt of the Sphinx

The Marquis’ Greek vases

The Galerie Campana - Temporarily closed