The Palace of Sargon IIThe Cour Khorsabad

The Khorsabad courtyard displays the remains of a gigantic city built in under ten years in the late 8th century BC. In those days, the area that is now Iraq was part of the powerful Assyrian Empire. King Sargon II had a new capital built at Khorsabad near Mosul, but after the death of its founder the city lost its status as a capital. The vestiges of the site were not discovered until French archaeologists excavated them in the 19th century… resulting in the world’s first Assyrian museum at the Louvre and the brand new discipline of Near Eastern archaeology.

A new capital

King Sargon II reigned over the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC. In about 713 BC, he made a radical decision intended to assert his authority: he founded a new capital. He chose a sprawling site at the foot of Mount Musri in the north of present-day Iraq and called it Dûr-Sharrukin, the ‘fortress of Sargon’. Taking advantage of the spoils and prisoners of war, the king undertook the construction of the largest city in the ancient world, a symbol of his omnipotence, with a palace comprising some 200 rooms and courtyards.

An unfinished city

King Sargon II died in a bloody battle in 705 BC and his body was never found. The mystery of his disappearance led to fears of divine punishment, so his son and successor, King Sennacherib, decided to establish his capital in Nineveh, where he was already acting as regent. He abandoned work on the unfinished city of Khorsabad, and the site was gradually forgotten, not to be rediscovered until the pioneering excavations conducted in 1843 by Paul Émile Botta, the French vice-consul in Mosul. This marked the beginning of Mesopotamian and Near Eastern archaeology. The excavation of Khorsabad led to the rediscovery of a lost civilisation, known only from the Bible and other ancient texts. Some of Botta’s finds were exhibited at the Louvre, where the world’s first Assyrian museum was inaugurated on 1 May 1847.

Royal decoration…that has faded with time

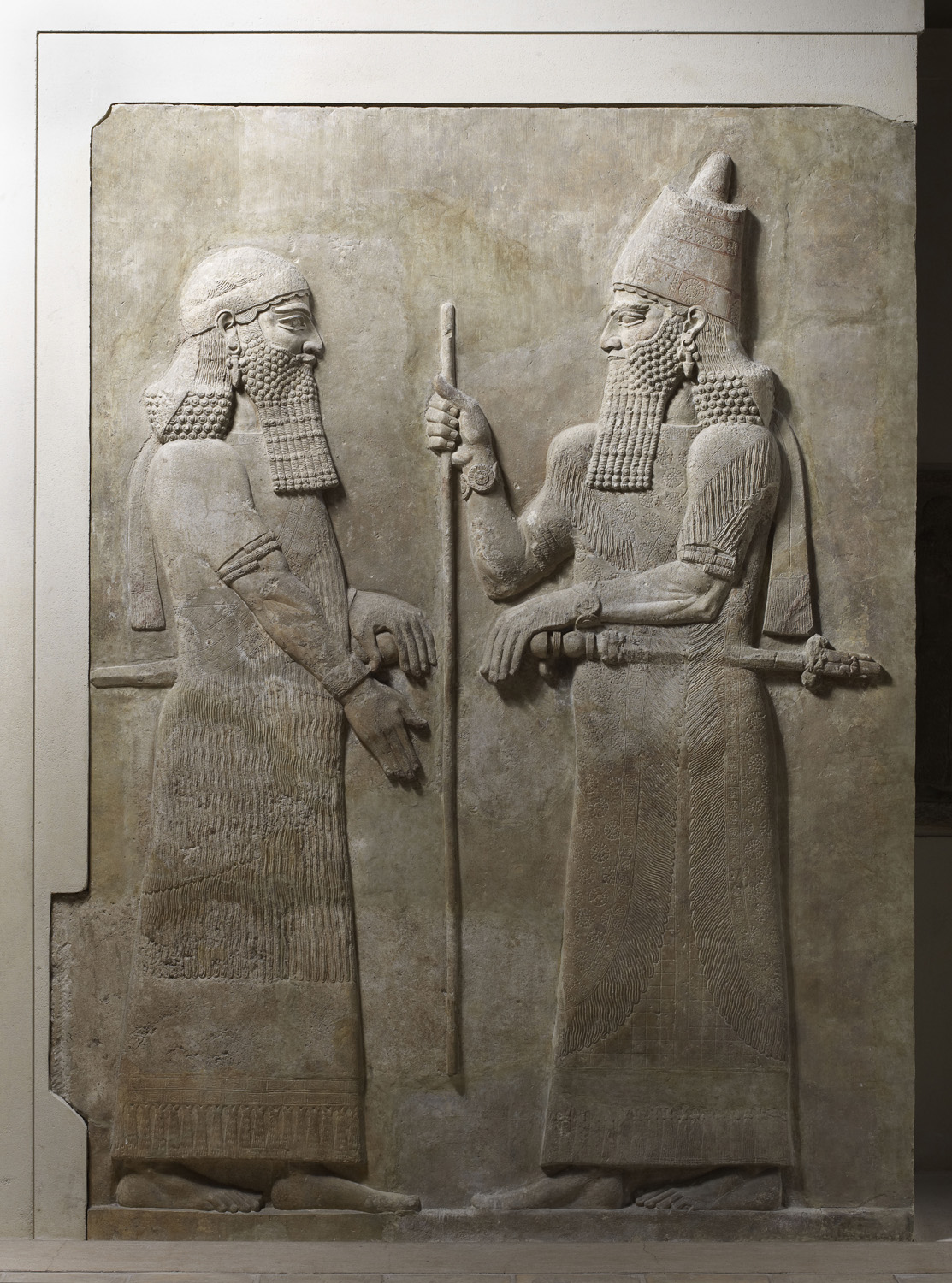

Daylight from the courtyard’s glass roof plays on the large carved stone slabs, many of which originally stood in an open-air courtyard. A number of them once decorated the main courtyard leading to the throne room in the huge palace of Sargon II. These alabaster slabs adorned the base of the brick walls and were painted in bright colours, blue and red in particular. Traces of colour are still visible, especially on the king’s crown. The low-relief carvings depict a variety of scenes (archers hunting, dignitaries parading) that glorified King Sargon II and illustrated life at his court. Some panels seem to show the transport of cedar wood from Lebanon for the construction of the new capital; these scenes recall the scale and speed of the building project and the extent of the Assyrian Empire, which encompassed a vast territory.

Protective genii

The palace’s sumptuous decoration also served a magical purpose. This was especially true of the protective genii carved on the walls: as their role was to watch over the city and its palace, they were carved at places which needed special protection, such as the doors. This is why the passageways are flanked by monumental winged bulls, each carved from a single gigantic alabaster block and weighing about 28 tonnes. These fantastic creatures, called aladlammû or lamassu, have the body and ears of a bull, the wings of an eagle and the crowned head of a human whose face resembles depictions of Sargon II. Their hybrid body and two or three sets of horns were signs of divinity in the Mesopotamian world. The lamassu combined the powers of the different animals in order to protect the city and its palace…and were benevolent creatures, as you can see from their gentle smile.

The Cour Khorsabad

YouTube content is currently blocked. Please change your cookie settings to enable this content.

Did you know?

Five-legged bulls

When viewed from the front, the bulls appear to be standing still with their back legs together. But if you look at them from the side, you will see that all four legs are depicted in a walking position...so these genii actually had five legs, and could appear to be either still or moving.

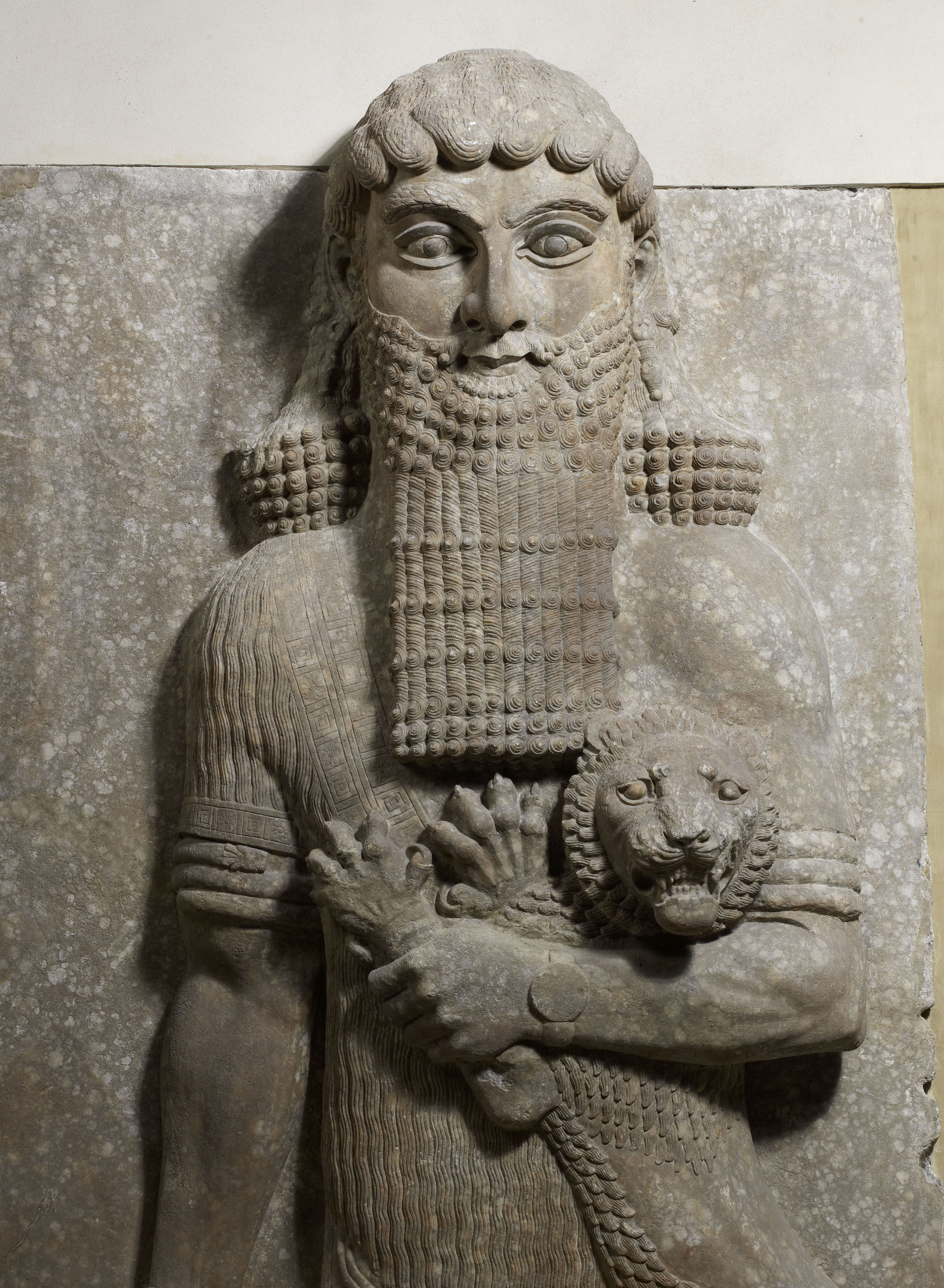

Gilgamesh

The figures in Assyrian art were generally shown in profile, so this frontal depiction is unusual: this male figure over 5 metres in height, effortlessly choking a furious lion, is a symbol of the king’s omnipotence. The hero has sometimes been identified with Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, whose legendary exploits are recounted in the oldest known texts and were popular throughout the ancient Middle East.

Gallery of works

Winged human-headed bull

1 sur 9

Delve a little deeper

Heritage of the Near East

In 2015, the French Ministry of Culture decided to invest in media resources to share knowledge and help preserve the heritage of the Near East. From Palmyra to the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus to Khorsabad to the Krac des Chevaliers, the aim of the project is to shed light upon the civilisations of the Near East, to allow the general public to learn about them and researchers to continue their studies in the field.

More to explore

Treasures of the Eastern Mediterranean

The Galerie d’Angoulême

An Introduction to Islamic Art

The Cour Visconti - level -2 closed