Ideal Greek BeautyVenus de Milo and the Galerie des Antiques

The Louvre’s gallery of antiquities, which replaced the royal apartments, displays masterpieces of Greek sculpture – including the famous Venus de Milo. You would need a heart of stone not to be moved by her grace!

From Milo to the Louvre

Together with the Mona Lisa and The Winged Victory of Samothrace, the Venus de Milo is one of the three most famous female figures in the Louvre. Her name comes from the Greek island of Melos (now called Milos), where she was found in 1820 and acquired almost immediately by the Marquis de Rivière, the French ambassador to Greece at that time. He then presented her to King Louis XVIII, who donated her to the Louvre in March 1821. In barely two years, the Venus had moved from the shadows to the light.

Aphrodite or Amphitrite?

When she first arrived at the Louvre, it was suggested that her missing arms should be restored, but the idea was eventually abandoned for fear of changing the nature of the work.

The lack of arms made it hard to identify the statue. Many depictions of Greek gods and goddesses contain clues to their identity in the form of ‘attributes’ (objects or natural elements) held in their hands, so this sculpture poses a problem: is she the sea goddess Amphitrite, particularly worshipped on the island of Melos? Or is she Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, as might be suggested by her sensual, half-naked body? This second argument, and the jewellery she once wore, tipped the scales in favour of Aphrodite (‘Venus’ for the Romans). Another possible clue was found near the statue: a hand holding an apple – an attribute of Aphrodite – carved from the same Parian marble.

The Venus de Milo

YouTube content is currently blocked. Please change your cookie settings to enable this content.

The Galerie des Antiques

The Venus de Milo can be admired today in the last of a long series of rooms where she stands in almost solitary splendour. The magnificent red marble decoration dates from the early 19th century and the reign of Napoleon I.

In 1807, the emperor bought the prestigious art collection of his brother-in-law, Prince Camille Borghese. To house the collection, he commissioned the architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine to enlarge the recently created Galerie des Antiques.

Like the first part of the gallery, the new rooms replaced the royal apartments – but Percier and Fontaine changed their layout completely, demolishing partition walls to enlarge the space and adding grey and red marble to set off the whiteness of the statues. The inauguration took place in 1811, ten years before the arrival of the Venus de Milo.

Make way for the goddess!

The Venus de Milo entered the Louvre in 1821 but her location within the museum has been changed several times. Unsurprisingly, she was first placed in the Galerie des Antiques, where she can still be admired today. But a number of questions arose: should she be displayed alone or among other artworks? What kind of base should she stand on and in what kind of setting? Wouldn’t she look better among the paintings in the Grande Galerie? Finally, after almost 200 years, the Venus was returned to the room where she had first been displayed – and now she has pride of place, standing almost alone in the middle of the exhibition space to allow visitors a better view.

To sum up!

The Louvre’s collection of Greek and Roman antiquities was installed little by little. The process began in 1692 when Louis XIV displayed some of his sculptures in the Salle des Cariatides. The year 1798 saw the arrival of other antiquities, confiscated during Napoleon’s military campaigns in Italy. The summer apartments of Anne of Austria were converted to create the Galerie des Antiques. Napoleon I bought the collection of his brother-in-law Prince Camille Borghese in 1807, then had the gallery expanded to include the nearby rooms which now house the Venus de Milo, among other masterpieces.

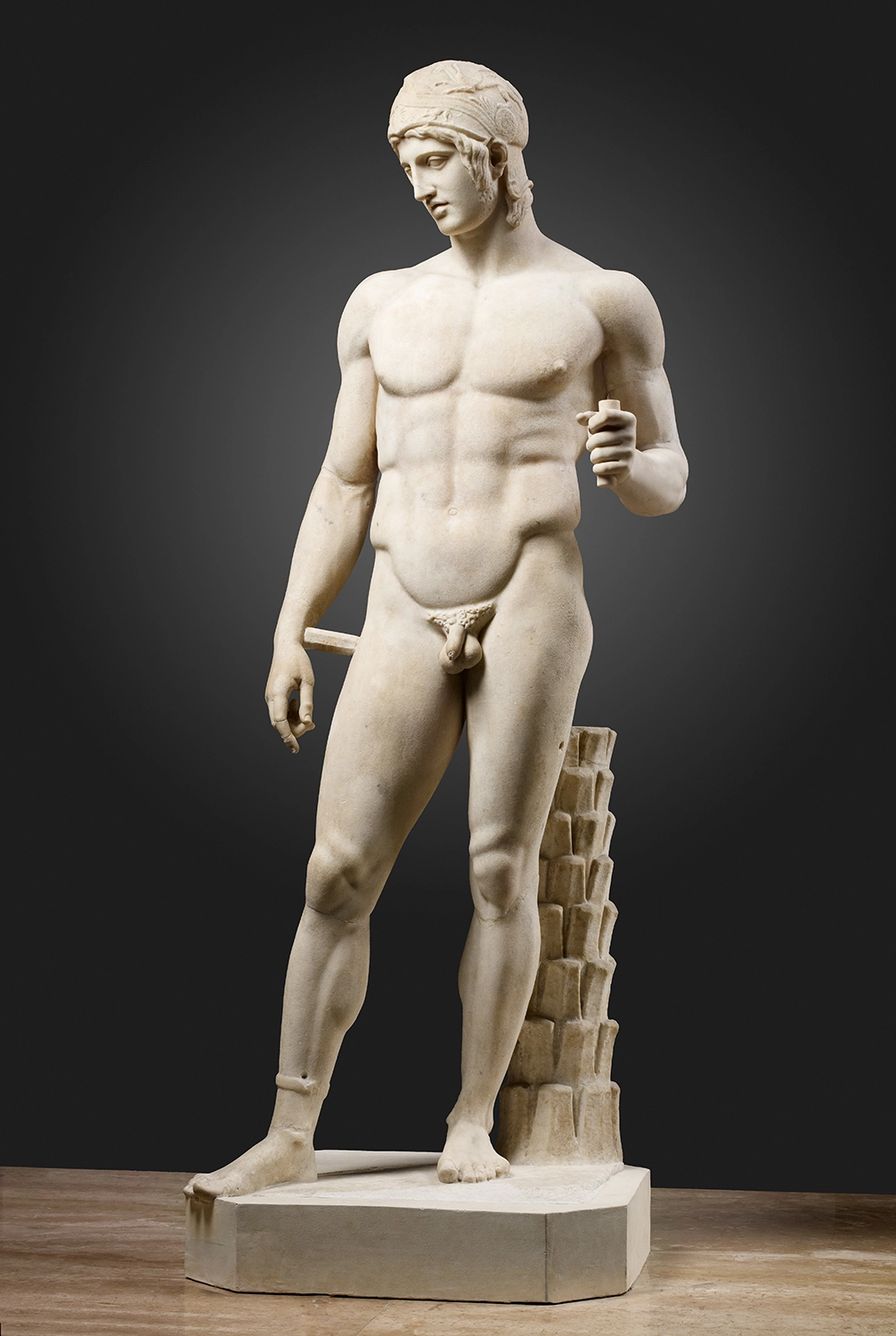

Greek sculpture masterpieces

Aphrodite, known as the 'Venus de Milo'

1 sur 11

Did you know?

A statue in several parts

Like many classical statues, the Venus de Milo was carved from separate blocks of Parian marble. The body was sculpted in two parts; the join between the torso and legs is difficult to see, hidden in the drapery at the hips. We know from a mounting hole at the left shoulder that the arms were also carved separately then added to the torso. Other sculptures in the same room show how separately carved blocks were joined together later.

An older sister

The Venus of Arles had embodied ideal classical beauty before the Venus de Milo arrived on the scene! She was also named after the place where she was found – in this case the Roman theatre of Arles in southern France, in 1651, during the reign of Louis XIV. Again, there was debate as to whether she was Venus or another goddess, but the Sun King, greatly impressed by the ancient masterpiece, decided that she was a Venus. He had the statue restored by the sculptor François Girardon, who endowed her with her traditional attributes: the apple (awarded by Paris to the most beautiful goddess) and the mirror.

More to explore

A stairway to Victory

The Daru staircase

At the Heart of the Renaissance Palace

The Salle des Caryatides