Three centuries of Italian sculptureThe Michelangelo Gallery

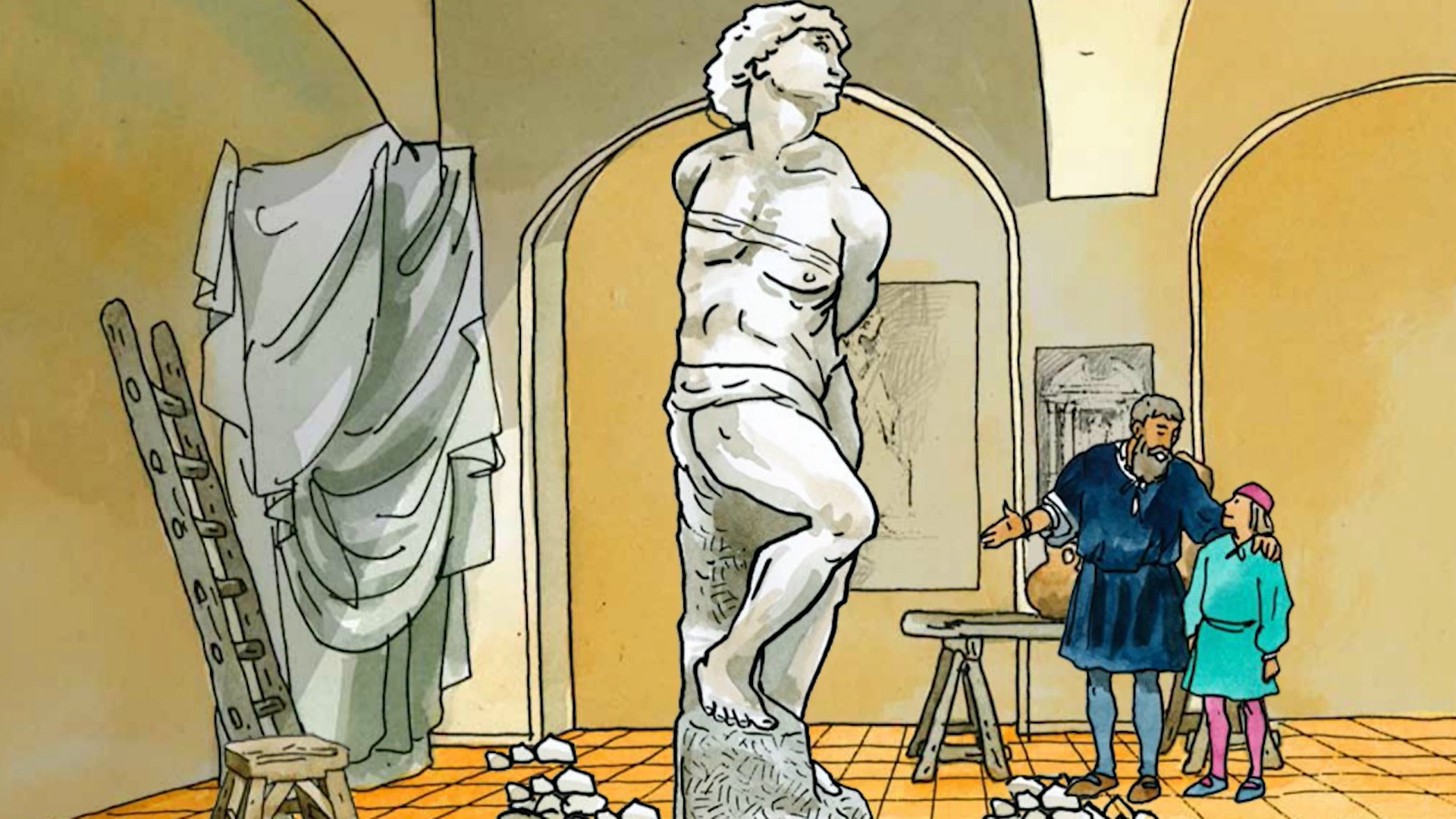

Named after the great Renaissance master, the Michelangelo gallery shelters masterpieces of Italian sculpture, including the artist’s famous Slaves. For close to three centuries, sculptors vied with one another to turn human emotion into stone.

A gallery for the new Louvre

During the Second Empire (1852–1870), the Louvre was abuzz with construction. At the time, the palace was both museum and seat of imperial power. Napoleon III had his architects, Louis Visconti and Hector Lefuel, build new spaces, some to house collections of art, like the Michelangelo Gallery.

Built between 1854 and 1857, this new gallery served above all a practical purpose: it was the official access to the Salle des États where major legislative sessions were held under the Second Empire. It was also the venue for sculptures during the annual Salon, a major artistic event of the time that gave living artists a chance to showcase their talent.

A stony decor

For his work, Hector Lefuel drew inspiration from his predecessor, the architect Pierre Fontaine. The latter worked at the Louvre under different political regimes all throughout the first half of the 19th century. His vision in the Salle des Cariatides and Galerie Angoulême inspired Lefuel to create the wide vaulting in the Michelangelo and Daru galleries, as well as the marble flooring in bold colours.

Large windows on either side of the gallery flood the space with natural light. This would not suit paintings, but is particularly flattering for sculptures in white marble, bronze or terracotta.

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

YouTube content is currently blocked. Please change your cookie settings to enable this content.

From Michelangelo to Canova

The Michelangelo Gallery now offers an overview of Italian sculpture from the 16th to the 19th century. It owes its name to the Florentine artist Michelangelo, who steals the show with his Slaves, two masterpieces which were part of an unfinished project for the funerary monument of Pope Julius II. Before even entering the gallery, visitors can admire from afar the so-called Dying Slave, in a stunning play of perspective. The Slave is set against a monumental portal behind him, decorated with the figures of Hercules and Perseus. Originally erected in the Palazzo Stanga di Castelnuovo in Cremona, its form recalls that of an ancient triumphal arch.

Other denizens of the gallery include Flying Mercury by Giambologna, a sculptor born in Flanders who enjoyed great success in Florence, and Mercury Abducting Psyche by his pupil Adriaen de Vries. Before leaving the gallery, visitors can admire Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss by Canova, a tour de force in marble. The artist’s expert hands perfectly rendered Cupid’s soft flesh and ardent passion.

Masterpieces

Benvenuto Cellini, The Nymph of Fontainebleau

1 sur 11

Did you know?

The wandering Slaves

Michelangelo’s Slaves were made for the funerary monument of Pope Julius II, who died in 1513. But this grandiose project was deemed too costly by the pope’s successors. So Michelangelo gave the two statues to his friend Roberto Strozzi, a Florentine in exile at the French court. Strozzi in turn gave them to King François I. But the story doesn’t end there. The new king of France, Henri II, offered the works to the High Constable of France, Anne de Montmorency, who brought them to his château in Écouen. Less than a century later, the statues moved again, when in 1632 Cardinal Richelieu purchased them for his own home, aptly called the Château Richelieu. For close to 150 years, the Slaves stayed in the families of the cardinal’s heirs, until they were seized during the French Revolution and came to the Louvre in 1794. The trials and tribulations of the pair finally came to an end!

Cupid and Psyche

Psyche was a beautiful princess. So beautiful that Venus, the goddess of beauty, was furiously jealous of her. She ordered her son, Cupid, to punish the young girl. But Cupid fell in love with Psyche and carried her off to an enchanted castle. Everything seemed to be going so well for the couple, but Psyche broke a promise she made to Cupid and the god fled. Venus then gave Psyche a series of impossible missions to carry out, including going to the underworld and bringing back a beauty potion. Psyche managed to do it, but when she opened the bottle to take a sniff, she fell down lifeless. Fortunately, Cupid brought her back to life with a kiss. This is the moment Canova chose to depict. Adriaen de Vries, a Renaissance sculptor also inspired by this myth, chose to show what happened next. On the order of Jupiter, Mercury – the messenger of the gods – carried off Psyche (who is still holding the beauty potion in her hand) to the heavens where she was granted immortality. Through this story, the sculptor symbolically represents art, embodied by Mercury, which elevates the soul, ‘psyche’ in Greek, to an immortal state.

More to explore

Treasures of the Eastern Mediterranean

The Galerie d’Angoulême

Italian painting in perspective

The Grande Galerie