A masterpiece of the Louvre

13 February 2023

As part of its contemporary programs, every Thursday, the Louvre invites creative figures who have accompanied it to choose a work from its collections and present it to its digital audiences.

A masterpiece of the Louvre

13 February 2023

As part of its contemporary programs, every Thursday, the Louvre invites creative figures who have accompanied it to choose a work from its collections and present it to its digital audiences.

The writer and lawyer Robert Badinter, former Minister of Justice, who was a guest of the Louvre in 2005. He gives in insights on Le Chancelier Séguier by Charles Le Brun (1660-1661).

"Power and glory": this aphorism comes to mind as we face Charles Le Brun's admirable painting, which depicts the procession of Chancellor Seguier riding in majesty, surrounded by squires on foot (1660-1661). In what solemn circumstances was it created? According to tradition, it was during Louis XIV’s return to Paris after his marriage to the Infanta Maria Theresa, celebrated in Saint-Jean-de-Luz on August 26, 1660. There was no need to include any additional dignitaries to embody absolute royalty. The Chancellor was the first of the great officers of the kingdom - he sealed the acts, presided over the councils in the absence of the sovereign. Irremovable from his position, even if the king could remove the Seals, he embodied the permanence of the Monarchy.

The painter chose to represent the Chancellor in ceremonial dress at the center of the painting, riding a white horse. The escort of squires is present in the painting only to illustrate the greatness of the chancellor, the splendor of his crew, and beyond him, that of the King - his master. The Chancellor’s face, already aged, indecipherable, is less important to the painter than the eye of his horse, the gold woven brocade of his robe and the black velvet of his hat. The Chancellor thus represented by Le Brun symbolically testifies to the omnipotence of his master, Louis XIV. This is the political message expressed by the painting. Let us salute the masterpiece of the painter celebrating the glory of the Sun King through the pomp of Chancellor Seguier.

Robert Badinter

This week, artist Anselm Kiefer, author of a permanent décor at the Louvre in 2007, brings together two of Rembrandt’s masterpieces from the Louvre collection – Self-Portrait with an Easel and Meditating Philosopher.

Autoportrait au chevalet by Rembrandt shows the artist standing in front of his easel looking into a mirror or looking directly at the viewer. In one hand he holds a palette, which is partially obscured by the line of the stretcher running parallel to the canvas. In the other hand he holds a brush, which lies exactly on the diagonal line leading from the lower right to the upper left corner. We will discuss the diagonals crossing the canvas—which are always important in the paintings of the masters—later, when we look at the second painting by Rembrandt. For the moment I will just briefly note: the artist's head is exactly above the intersection of the two diagonals. (If you imagine the picture ends at the stretcher on the right side.)

What is special about all of Rembrandt's self-portraits are the eyes. They have particularly fascinated me since I could see. Again and again, on visits to museums (even as a schoolboy, looking at the self-portrait in Karlsruhe, which I wanted to copy on the spot), I let myself be drawn into these eyes. They are like a gentle vortex, a closing opening, a conflict between a mystery that reveals and seals at the same time.

Now let's add the second, smaller painting, Le philosophe en méditation. I have always seen these two paintings together, looking at them one after the other when visiting the Louvre. The connection was not due to any motives of content. The meeting of the two paintings happened more on a superficial formal level: the round of the self-portrait’s right eyeball portrait corresponds to the round as a whole in the painting of the philosopher. At the intersection of the two diagonals running against each other is the face of the philosopher, around whose brightness a darkness shadows the edges. This round then appears like the enlarged eyeball of the self-portrait. However, here the dark of the eyeball becomes the bright center in the picture of the philosopher. Just as brightness is inversely part of obscurity.

By penetrating, so to speak, the cornea of the artist's gaze, I see a strange mystical architecture behind the eye that simultaneously opens and closes. The philosopher's head is at the intersection of the two diagonals. The philosopher sits there calmly, while around him lies an astonishing movement. A spiral staircase dominating the image points upward, while a door placed to the right of the philosopher points to a room below. Thus, the philosopher meditates on above and below, heaven and earth, perhaps walking through the Seven Heavenly Palaces of Merkaba mysticism. (Rembrandt was familiar with Jewish mysticism). And considering the fire at the lower right edge of the picture, it is not far from Athanor, the alchemical furnace.

I do not know how far you have followed me in penetrating the cornea of the eye of the artist’s self-portrait, but a picture does not just consist of its materials or intellectual references; it only arises in us through what we see, that which the artist himself has perhaps not yet considered. In this way it remains alive, evolving.

The artist Robert Wilson @bob___wilson, a guest of the Louvre in 2013, made drawings addressing a Cycladic sculpture.

Le visage derrière

C'est toujours l'espace derrière qui donne à l'espace devant sa puissance.

C'est l'espace derrière qui donne à l'espace devant son mystère. Le mystère est dans sa surface.

Chaque opposé a besoin de son opposé.

Le marbre est dur, mais la surface est douce. L'acier et le velours.

La ligne simple est toujours la plus difficile à dessiner, car il y a plus d'espace autour d'elle.

Souvent, une culture ancienne dessine ou réalise des œuvres très simples. Cette statue datant de 2700-2300 avant J.-C. date d'une époque précédant la richesse de la Grèce et la décadence de ses arts.

La figure féminine cycladique a très peu de lignes. Ce sont des lignes nettes avec quelques détails stylisés, seuls le nez et la poitrine sont sculptés. La tête est inclinée en arrière et regarde vers le haut. On sent que le regard des yeux est dirigé vers l'arrière de la tête.

Pour moi, ce personnage est un gardien des morts, de nos ancêtres. Sa culture n'existe plus, et nous ne pouvons pas expliquer la figurine. Notre imagination est laissée libre, et elle continue à nous fasciner.

The artist and designer Martin Szekely (www.martinszekely.com), who conceived the museum’s new furniture project in 2021, comments on Michelangelo’s Slaves.

MICHELANGELO’S SLAVES OR THE PARTITION OF THE WORLD

Here is a conversation between a former Director and CEO of the Louvre and a young curator. It appears that neither of them have practiced sculpture. And yet, they seem to know all about the "slaves" carved in monumental blocks of marble five hundred years ago by Michelangelo. The chisel strokes intentionally left visible are traces of the technique; from them one can deduce the width of the chisel and the force applied by the sculptor's arm extended with the hammer. In the 16th century, long before noisy mechanization, man and tool were one in the same effort. The man of letters, deprived of the experience of making, uses the vocabulary of matter to explain his purpose - with the help of a metaphor. For the man of the making, an inappropriate use of what constitutes him seems to come from it, an impoverishment of his universe. According to Virgil, the Greeks "at the time of their splendor had only contempt of work, only the slaves were authorized to work: the free man knew only the exercises of gymnastics and the games of the spirit. The philosophers of antiquity taught the contempt of work – a degradation of the free man; the poets sang idleness – a gift from the gods: "O Meliboeus, this idleness is the gift of god". People exercising manual work, like craftsmen, were not well considered because they did not devote much time to an idleness manifested by the participation in theatrical, sporting or political activities. The slave who by definition was an instrumentum vocale (the slave at the disposal of the master: a speaking tool), could not remain inactive because he was destined only to the material productive action." In this case, Michelangelo is the one working. Is he a slave?

Martin Szekely

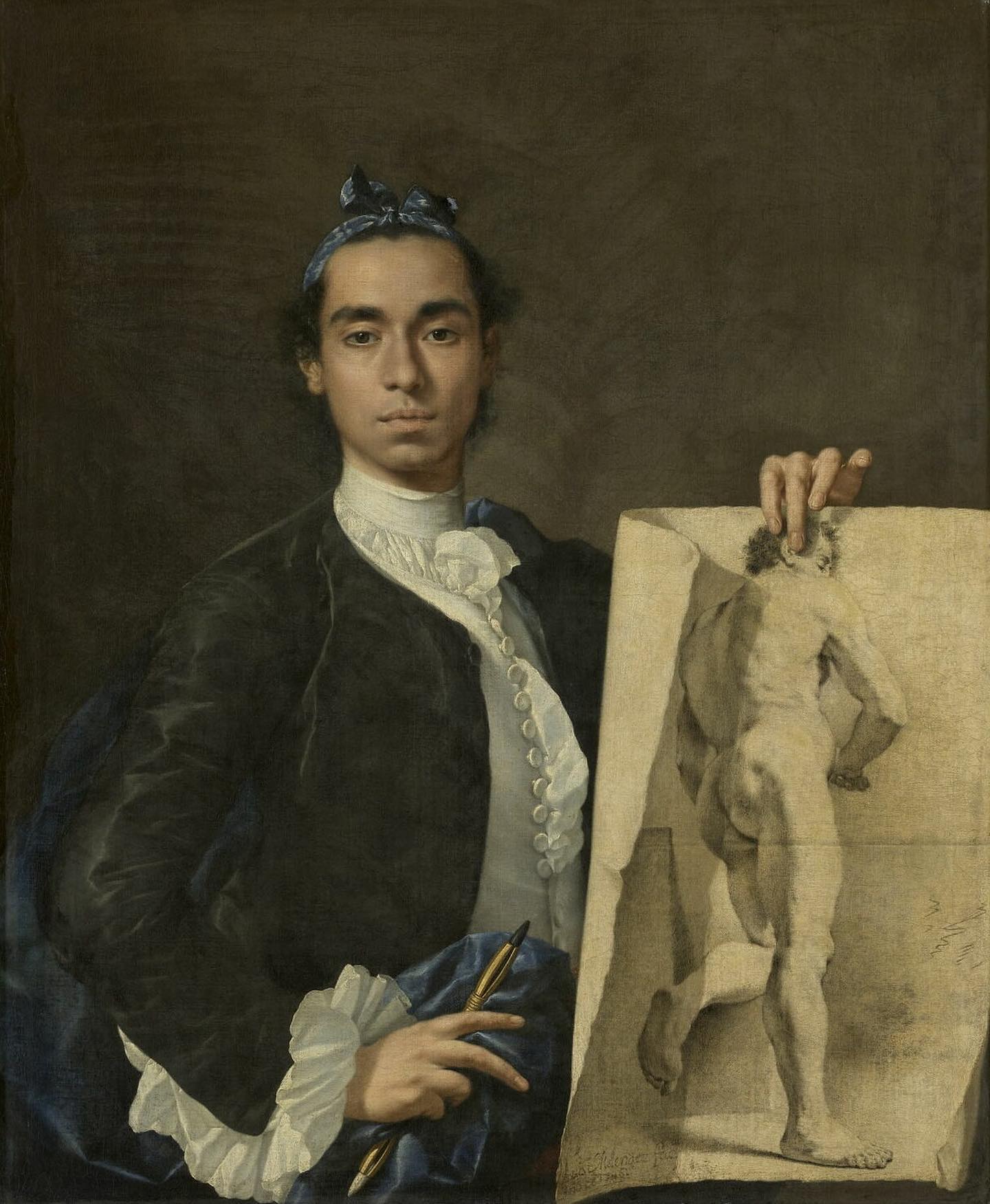

The painter Miquel Barceló, a guest of the Louvre in 2004, gives his insights on Luis Egidio Melendez’s Portrait of the Artist (1746). His work is currently displayed in the exhibition Les Choses.

This self-portrait at the age of thirty is the amazing work of the greatest painter of the Spanish Bodegón genre, as well as his only painting in which visible human figures appear (although with x-ray portraits come out under some of his best still-lives).

Luis Egidio Melendez, son, nephew and brother of extremely gifted painters and miniaturists, was trained from birth to be a kind of Messi of painting - the painter of the Casa Real.

The self-portrait in the Louvre shows him at a time when everything was still possible. Ambitious and spirited, he shows off his drawing like a bullfighter raises his capote. The young Luis Egidio is quite unafraid...

His painting is 1/4 portrait, 1/4 trampantojo or trompe-l'oeil, 1/4 draperies and 1/4 darkness...

Shortly afterwards, he was expelled from the young San Fernando Academy in Madrid and his career was to be a series of setbacks and rejections at the post he had longed for since his birth: to become the official king’s painter.

Despite this, he was to receive commissions – some almost humiliating, such as these 44 paintings of products of the Spanish land: swallowing his bitterness, he produced masterpiece after masterpiece.

The few scholars who have researched Melendez' work point out that there is almost no technical evolution in his painting; that from the beginning he painted in a certain extremely meticulous way that never changed... Except that, if you look at the table edges that invariably highlight his bodegóns, they are at first smooth and straight, then with time and rejection letters, they become filled with dings and nicks. Just as Billy the Kid marks the butt of his gun with every kill: our artist does this with every hit.

Melendez arrives at modernity by a different route than Velazquez or Goya. Like Yasujiro Ozu, he puts his point of view very, very low, at the height of a child or a man sitting on the ground, his nose almost on his models who also have his history glued to them.

We see blows, cracks and rough and harsh textures.

His self-portrait, which precedes his work, is the fresh, smooth and perfect fruit before hail, wasps and life mark it definitively.

Miquel Barcelo

The painter Yan Pei-Ming who in 2009 conceived The Funerals of Monna Lisa, then presented at the Louvre and now part of the collection of Louvre Abu Dhabi, where it is currently displayed. Yan gives his insights on the Monna Lisa.

The Mona Lisa was a common image when I was very young in China. Leonardo da Vinci is, of course, very famous there. There has never been an artist's work as popular as the portrait of Mona Lisa. It is both a myth for artists and a popular myth. The first thing the public wants to see at the Louvre is the portrait of Mona Lisa. If you haven't seen it, you haven't been to the Louvre. Leonardo spent four years working on this portrait. It is a model of a portrait - it has everything: the hands, the smile, the hair, the landscape. It's like a window. When I was invited to the Louvre, the Mona Lisa was my first idea. At the time, I exhibited in the Denon rooms, behind the real Mona Lisa, like a shadow. Instead of making a gray shadow, I added all the details. The landscape behind the portrait of Mona Lisa has been the object of much research by scholars: I immersed myself in her imaginary world.

Yan Pei-Ming

The photographer Candida Höfer, a guest of the Louvre in 2009, comments on the Guan Yu okimono.

It was during a cursory walk in the Richelieu Wing looking for motives that I passed a vitrine filled with porcelains and what I assumed were Netsuke. Being interested in all things Japanese,I stopped briefly and was captured by a small figure in the corner that I later identified as an okimono.

The figure gave me what I interpreted as a skeptical look probably criticizing the haste with which I had walked through the Museum. The figure was so full of detail that I looked closer. The posture I thought was that of a man who was just going to make a challenging remark. Then I noticed he was hiding something behind his back, a weapon. At the same time, he seemed benevolent, almost a little humorous about my fear.

Candida Höfer

The artist Xavier Veilhan, a guest of the Louvre in 2021, comments on an Egyptian basket.

These fragile baskets are almost 3500 years old. Yet, the heather rattan they are made of is in perfect condition, preserved in the dry sand. This line of flexible material becomes a three-dimensional object. It can then contain others, gather them and order them. It is a utilitarian object that is still made and used today. Its manual fabrication involves the repetition of the same knot, like a precursor to the industrial and digital age. I am moved by the modesty, the everydayness and familiarity of this object, whose presence allows me to imagine what happens off-screen.

Xavier Veilhan

The artist Chéri Samba, a guest of the Louvre in 2015, comments on Arcimboldo’s Winter.

There are different Artists that I like very much, whose work I admire and who I consider to be truly remarkable, especially for their great capacity for imagination and inspiration. Because, in order to produce and present something, one must first imagine or be inspired. I also admire their drive to produce their thoughts with extraordinary finishes. Among these Artists is the great Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

I first discovered the work of the Artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo in a book, in Brussels. I could not believe it. I leafed through the book several times and still could not believe it. How beautiful it was to see what I saw! It was truly impressive... and I decided to make an Arcimboldo myself, as I had done in the past for another great Artist, whose name I refuse to mention.

No matter how long it would take me, I wanted to show my ability to reproduce such a strong work. My father often told me that I had to dream big and walk with the greats to progress and not end up like an old child. So, I followed his example and challenged myself to paint as well as he did. And so I allowed myself to reproduce - as I had also done for the artist whose name I omitted - one of Arcimboldo's paintings: Winter, from the series of the four seasons, which I entitled Stupor.

For me, Arcimboldo remains one of the great thinkers in painting, one of the examples to follow - while retaining all our diversity, of course.

I thank the Louvre and all those who encouraged me to speak about my admiration for Arcimboldo.

Chéri Samba

The artist Isabelle Cornaro, guest of the Louvre in 2015, comments on a Parthian-Babylonian figurine.

I first saw this impressive figurine in 1993, when I was studying at the Louvre, and I thought about it long enough to develop an intimate relationship with it.

I had learned that it came to the museum as a gift from Pacifique-Henri Delaporte, a collector and consul who served successively in Tunis, Cairo, and Baghdad, at the height of the second French colonial empire.

Frontal, subtle, highly auratic, the figure presents a complex relationship between the simplified line of the silhouette and the diffuse soapy white of the alabaster - the mind slides infinitely from the outline to the material, to the outline again; and if one were to isolate the jewels placed in the navel, the neck and the hair, they would form an abstract landscape that crosses the body in a remarkable geometry. They seem to give her a non-human stature, half deity, half animal.

She accompanies, in the tomb where she was discovered, the Babylonian Parthian goddess of love and war, Nanaya - of whom it is written that "justice walks constantly” at her side. I love the names of the countries she is linked to: Akkad, Sumer, Babylon, and their ancient cities, Ur, Uruk, Susa, Nineveh, situated on the border of Iraq and Iran.

Isabelle Cornaro

The artist Mark Manders, guest of the Louvre in 2015, comments on Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with Saint Ann.

Virgin with Child with Saint Anne, Leonardo da Vinci, 1501-1519

When I was about 20 years old and making my first works as an artist I put my money together to be able to travel to Paris and spend 4 days at the Louvre. Intensively studying the works of the collection became a very important foundation for my work as an artist but also for my development as a person. For me ‘Virgin with Child with Saint Anne’ made such a huge impact:

Da Vinci’s breathtaking composition is a magnificent communication of love from the top down. Whenever I see this painting, I catch myself thinking that the woman at the back and the woman at the front are actually one and the same person and that together they are displaying a movement full of love.

The fact that this work is described as unfinished changed the direction of my own work. From then on I only made unfinished rooms…

Mark Manders

The artist Monique Frydman, guest of the Louvre in 2013, comments on Sassetta’s The Virgin and Child surrounded by six angels.

"The Virgin and Child surrounded by six angels" by Sassetta.

Panel of the Polyptych of Borgo San Sepolcro.

It was in the restoration studio of the Louvre that I first discovered it. I see her - the Virgin, this unattainable woman - so close, still alive with the one who painted her for us just yesterday, Sassetta. And this blue, that with infinite delicacy the restorer caressed with the tip of her fine brush to revive its brightness - the divine blue of the mantle.

She is here, soft, confident in her blue dress, enveloping us in her radiant majesty - a very young and modest woman astonished in her golden aura. He is the Child, full of tenderness for her. They are the six angel musicians who smile and carry us away in their divine music. As in a golden shell, happiness resounds. This work, however, had a tragic fate: the Polyptych was dismantled, its panels scattered and some were even destroyed. Little by little, only very recently, attempts to reconstitute the Polyptych have been attempted here and there.

It is my madness to want to remake and re-member it myself. For me, a contemporary painter to dare to confront the masterpiece whose absence turned it into a dream! My "Sassetta Polyptych" was exhibited in the Louvre’s Salon Carré, facing the Florentine masters of the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries.

Monique Frydman

The Portrait of King Charles I of England, by Anthony van Dyck, returns to the gallery walls after over a year of conservation treatment. Blaise Ducos, Curator of Flemish and Dutch Paintings, discusses this masterpiece.

5 February 2025

Tuileries Garden Benches Sponsorship Campaign

The Louvre is launching a long-running operation in benefit of the historical benches that have been present in the Tuileries Garden since the 19th century. This campaign aims to support an ambitious project to restore and recreate the iconic benches of the largest garden in Paris, in order to improve the visitor experience.

24 December 2024

The conservation treatment of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, funded by the 2018 'Become a Patron!' campaign, began in November 2022 and will be completed before the summer of 2024. This restoration aims to return the monument to its former glory.

5 October 2023